What is language? What is the meaning of words? Is a private language possible? Do words such as mind, consciousness, and even pure logic and mathematics have any existential meaning? Basic history and discussion from the working class perspective of issues in philosophy of language, science, existentialism, and pragmatism. The emphasis is on how dominant philosophies have and do affect the working classes throughout history because this is the group of people who suffer the worst and adverse affects of whatever are the dominant philosophical ideals of any given age and who usually are the least knowledgeable about the nature of the ideals and why they are dominant. Theology is studied as a branch of philosophy and not as religious theology.

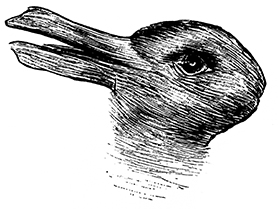

A Duck-Rabbit

My Parisian wife and mother-in-law

Quine’s Fabric

Quine’s eloquent description:

The totality of our so-called knowledge or beliefs, from the most casual matters of geography and history to the profoundest laws of atomic physics or even of pure mathematics and logic, is a man-made fabric which impinges on experience only along the edges. Or, to change the figure, total science is like a field of force whose boundary conditions are experience. A conflict with experience at the periphery occasions readjustments in the interior of the field. Truth values have to be redistributed over some of our statements. Re-evaluation of some statements entails re-evaluation of others, because of their logical interconnections; the logical laws being in turn simply certain further statements of the system, certain further elements of the field. Having re-evaluated one statement we must re-evaluate some others, whether they be statements logically connected with the first or whether they be the statements of logical connections themselves. But the total field is so undetermined by its boundary conditions, experience, that there is much latitude of choice as to what statements to re-evaluate in the light of any single contrary experience. No particular experiences are linked with any particular statements in the interior of the field, except indirectly through considerations of equilibrium affecting the field as a whole.

If this view is right, it is misleading to speak of the empirical content of an individual statement, especially if it be a statement at all remote from the experiential periphery of the field. Furthermore it becomes folly to seek a boundary between synthetic statements, which hold contingently on experience, and analytic statements which hold come what may. Any statement can be held true come what may, if we make drastic enough adjustments elsewhere in the system. Even a statement very close to the periphery can be held true in the face of recalcitrant experience by pleading hallucination or by amending certain statements of the kind called logical laws. Conversely, by the same token, no statement is immune to revision. Revision even of the logical law of the excluded middle has been proposed as a means of simplifying quantum mechanics; and what difference is there in principle between such a shift and the shift whereby Kepler superseded Ptolemy, or Einstein Newton, or Darwin Aristotle?

The Rule-Following Paradox (“RFP”)

The philosopher Saul Kripke created the following mathematical example of the RFP:

Suppose that you have never added numbers greater than 50 before. Further, suppose that you are asked to perform the computation 68 + 57. Our inclination is that one will apply the addition function and calculate the correct answer as 125. But now imagine that a skeptic comes along and argues:

- There is no fact about your past usage of the addition function that determines ‘125’ as the right answer.

- Nothing justifies you in giving this answer rather than another.

After all, the skeptic reasons, by hypothesis you have never added numbers greater than 50 before. It is perfectly consistent with your previous use of ‘plus’ that it and the acts resulting from it meant and mean the ‘quus’ function, defined as:

The skeptic argues there is no fact about known reality that determines one ought to answer ‘125’ rather than ‘5’. Your past usage of the addition function is susceptible to an infinite number of different quus-like interpretations. It appears that every new application of ‘plus’, rather than being governed by a strict, unambiguous rule, is actually a leap in the dark.

Indeterminacy of translation:

Indeterminacy of translation refers to the inability to ever fully translate the meaning of a word from one language to another. While this refers mainly to translation between natural languages, it can also refer to individuals using the same language trying to understand one another’s full meaning.

When approaching the problem of understanding a word, there are two parts that must be taken into mind. There is the sound of a word, which can be referred to as the “phonetic part”. In this part, an individual learns the proper way to vocalize the sound of the word. Then there is the more complex part of the word which relates to its actual meaning, and that is known as the “semantic part”. When an individual speaks the word that he has phonetically learned, he then refers to something outside of himself. Usually this is a reference to an object, though it can also be a more abstract reference to an idea. When it comes to learning the semantic part, though, more is required than just hearing the sound. One must be able to “see what is stimulating the other speaker” (Quine 28). When words refer to abstract ideas, there can be a problem, because the meaning of words can be determined by an individual’s mindset and experiences. Therefore, even when speaking the same language, two individuals can be speaking about the same thing but have a different idea of it in their minds and therefore not be able to fully communicate about it.

Indeterminacy is something that can be seen even more apparently with differing languages. Quine uses the example of the foreign word “gavagai,” which is uttered when a native speaker points at a rabbit. A linguist trying to understand the language has to decide whether the native speaker’s utterance means “rabbit,” “undetached rabbit parts,” or “rabbit stages” (Quine 32). The problem is that in the native language, there may be a different system of reference than in our language, and so there may be words that mean more than one thing, just as we have words that can have an exact referential meaning and a more “abstract singular term” at the same time (Quine 38). While the physical ostension that a native makes to an object when she says a word can be noted, it cannot be known for sure what she is speaking about without understanding the conceptual foundations that the language exists upon (see inscrutability of reference). Therefore, while translations can be inferred with a decent amount of accuracy, there is never a certainty that all meanings are understood in all contexts.

–Robert Seeloff II

Source:

Quine, W. V. O. Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press, 1969.

Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience

“Sand Pebbles” music courtesy the film, Sand Pebbles, music by Jerry Goldsmith.

![{\displaystyle x~\mathrm {quus} ~y={\begin{cases}x+y&{\text{if }}x,y<57\\[12pt]5&{\text{otherwise}}\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/44be7e9bc58555cbf2f304a98dde3b832aca100d)